BY: Robert Jowaiszas, Community Editor/Reporter

Long before the first highway cut across the county and decades before commuters lined up at bridge tolls, the Hudson River was Rockland’s true Main Street. The shoreline communities of Nyack, Haverstraw, Piermont, and Stony Point grew up facing the water for a reason. The river was the way goods moved, the way people traveled, the way news arrived, and the way local families made their living. What is now a landscape of marinas, parks, and restaurants was once a working shoreline where the ringing of hammers and the scent of fresh-cut timber signaled that another vessel was taking shape.

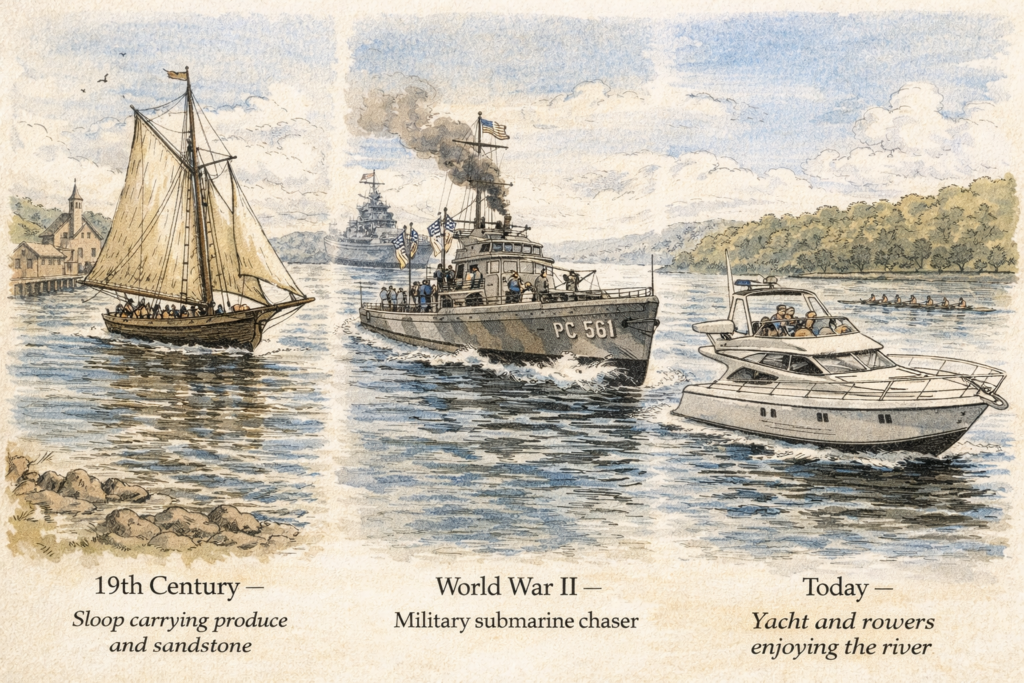

In the first half of the nineteenth century, Nyack became the most active sloop-building center on the Hudson River. The village waterfront was crowded with shipyards turning out wooden cargo boats that would carry Rockland’s products south to New York City and return with supplies and passengers. The work drew carpenters, blacksmiths, riggers, and sail makers, and entire neighborhoods formed within walking distance of the docks. Among the most respected builders was James B. Voris, whose vessels were known for their strength and reliability and whose output helped establish the reputation of local craftsmanship throughout the region. Launch day was a community event. Families gathered along the shore as a finished hull, freshly painted and rigged, slid into the river and began its working life.

If Nyack was known for building the boats, Haverstraw was known for filling them. At the height of the brick industry, the riverfront there became a floating extension of the yards and factories on shore. Barges stretched out into the current waiting for the tide and the tow south. A single load could carry hundreds of thousands of bricks, bound for the streets and buildings of a growing New York City. The men who worked those boats often brought their families with them, living onboard through the shipping season and tying up along the same docks day after day until a tight-knit river community formed between water and land. The Hudson was not simply scenery; it was the workplace, the marketplace, and the road home.

The arrival of regular steamboat service in the 1820s transformed the rhythm of life along the river. For the first time, the trip to the city followed a dependable schedule, and businesses clustered near the landings to meet the daily flow of passengers. For many years the quickest and most reliable route between Rockland and Manhattan was by water, and the downtown streets that still run toward the shoreline reflect the location of those long-gone docks.

Boatbuilding continued into the twentieth century, evolving with the times. In Upper Nyack, the yard operated by Julius Petersen became known for elegant private yachts that drew wealthy owners to the river, and then, during World War II, shifted almost overnight to the urgent work of national defense. Hundreds of local residents found employment there building naval rescue craft and submarine chasers. Once again the Hudson served as a lifeline, and the quiet river town became part of a global effort.

The industrial era eventually faded as railroads, highways, and trucking replaced river freight and the brick industry declined. The great yards closed, the barges disappeared, and the waterfront grew quieter. Yet the river never lost its hold on the community. In the late 1960s the environmental sloop Hudson River Sloop Clearwater sailed into view and helped a new generation see the Hudson not as a shipping lane but as a natural treasure worth protecting. Where shipways once met the tide, people now gather for concerts, walks, and sunsets.

It takes only a moment of imagination to see the earlier scene. Where pleasure boats rock at their slips today, masts once filled the sky. Where visitors stroll along the shore, ship carpenters once bent over their work and blacksmiths shaped iron fittings for the next launch. The outlines of the old economy are still visible in the streets that lead to the water and in the downtown business districts that grew up beside the docks. Rockland’s connection to the Hudson is not a backdrop to its history; it is the reason that history exists at all. The river built the boats, the boats built the towns, and the towns became the county we know today.

On quiet evenings, when the current moves south past Nyack and Haverstraw just as it did in the days of sail and steam, it is not difficult to picture a newly finished sloop easing into the channel while a crowd on shore watches with pride. The sound of the launch, the beginning of another working life on the river, was once the sound of Rockland itself.