From Rockland Historical Society

In 1609, Henry Hudson set sail aboard the Half Moon for the Dutch East India Company, hoping to find a shortcut to Asia. Instead, he sailed into a wide river that would bear his name — and unknowingly opened the way for Dutch settlement in what is now Rockland County, New York.

Hudson’s reports of fertile valleys, calm inlets, and friendly Lenape villages soon drew settlers north from New Amsterdam. By the mid-1600s, Dutch farmers and traders were establishing homes and trading posts along the Hudson River, particularly around Tappan, Nyack, and Piermont, laying the foundation for Rockland’s earliest communities.

Trading and Land Transfers

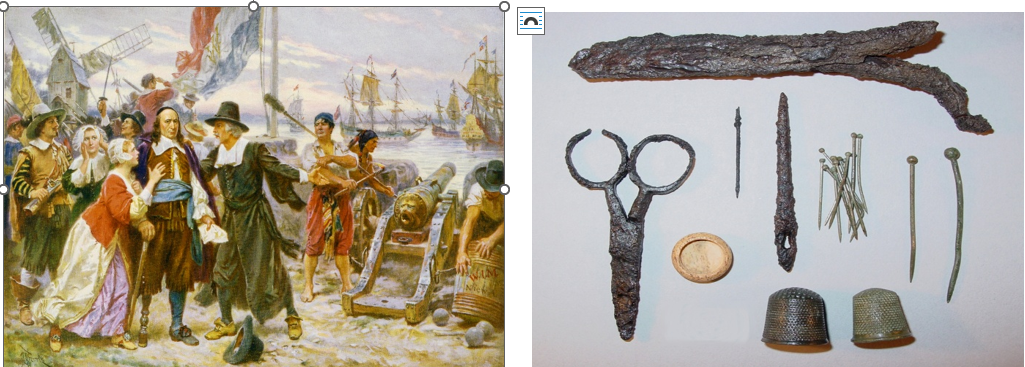

The Dutch first arrived as merchants, trading iron tools, cloth, and beads for the Lenape’s animal furs. The Lenape (Munsee) people, who had lived here for generations, viewed these exchanges as agreements to share land and coexist. The Dutch, however, recorded legal deeds claiming permanent ownership. Over time, stone houses rose where longhouses once stood, and fences divided fields that were once open to the Lenape. By the early 1700s, the Lenape had largely moved westward, replaced by Dutch farms and churches that defined the emerging European community.

The early Dutch settlers were practical and industrious. They built sturdy homes of local sandstone — one-and-a-half stories tall, with thick walls, low-beamed ceilings, and wide central fireplaces for cooking and warmth. Roofs often had the familiar gambrel shape, sloping outward to create overhangs that protected the walls from rain and snow. Many of these houses still stand today in Tappan, Blauvelt, and Clarkstown, their date stones carved with the initials of the original owners.

Farming was at the heart of family life. The Blauvelt, Haring, DeBaun, Dey, Van Houten, Tallman, and Onderdonk families raised cattle and pigs, grew corn, rye, and wheat, and produced butter and cheese that they ferried downriver to New York markets. Dutch barns, with wide doors and tall central aisles, became a familiar sight across the valley.

Inside, life was orderly and centered around family. Women managed households, made candles and soap, spun wool, and wove linen on wooden looms. Men tended livestock, mended fences, and worked the fields. Children helped early and learned both Dutch and English as the generations changed.

Dutch clothing in the Hudson Valley mixed practicality with tradition. Men wore knee-length breeches, wool stockings, and broad-brimmed hats, while women favored long skirts, aprons, and lace caps called mutsen. In winter, they bundled in heavy cloaks made from homespun wool. Sunday clothing was formal and neat, reserved for worship and family portraits, while everyday farmwork called for simpler, durable attire.

Religion guided daily life. The Reformed Dutch Church served as both a place of worship and the center of community life. The Tappan Reformed Church, founded in 1694, still stands today and is one of New York’s oldest congregations. Services were conducted in Dutch for more than a century, and churchyards recorded births, marriages, and deaths for local families.

Inland, the Clarkstown Reformed Church, organized in the early 1700s, became the spiritual anchor for settlers around West Nyack and New City. Families such as the DeClark, Demarest, and Van Houten clans helped establish it, and many of their descendants remain in the area today.

While most Dutch settlers were farmers, they also built small industries along creeks that powered gristmills and sawmills. Blacksmith shops repaired wagons, and ferry crossings carried goods to Manhattan and Tarrytown markets.

Dutch craftsmanship shows in the architecture. Thick sandstone walls kept homes cool in summer and warm in winter. Windows had small leaded panes, and doors were often split horizontally — the famous Dutch door, which let in light and air while keeping animals out. Furniture was handmade: long benches, heavy tables, and chests decorated with tulip motifs.

The Old ’76 House in Tappan began as a Dutch tavern and later held British spy Major John André before his execution. Nearby, the DeWint House, built around 1700, hosted General George Washington during the Revolutionary War. Other stone homes — including the Blauvelt, Van Houten, and Onderdonk houses — still stand as examples of Dutch design and longevity.

In Clarkstown, Dutch settlers-built farms along paths that became Kings Highway, Strawtown Road, and Demarest Mill Road. They created self-sufficient communities with farms, mills, and small businesses, following old Lenape trails. Although English gradually became dominant, Dutch customs, recipes, and values endured.

The Dutch sense of community, order, and faith shaped Clarkstown’s early government and agricultural success. Even as suburban development spread in the 20th century, stone walls, barns, and churchyards remain as quiet witnesses to their heritage.

The Dutch brought faith, skill, and resilience to Rockland County — and through recorded land transfers, they established a permanent European settlement on Lenape lands.

Today, visitors can walk the same fields where Dutch farmers once worked, stand beneath church steeples that have witnessed centuries, and admire stone houses that have survived generations. From Tappan’s historic taverns to Clarkstown’s quiet farm lanes.

Rockland County still carries the story of those early settlers who set out for Asia — and instead found a home along the Hudson.

Their story, like Rockland itself, is one of faith, family, and the enduring power of place.